The James Webb Space Telescope: a personal narrative

The Catalyst / Photo courtesy of NASA.gov

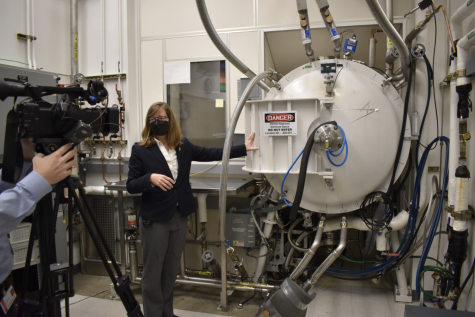

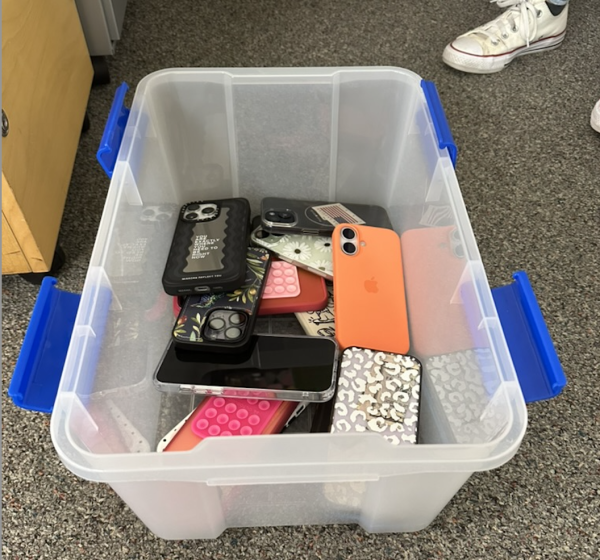

Dr. Alison Nordt and a team of NASA engineers unpack NIRCam upon arrival at NASA Goddard.

In 2009 I told my kindergarten teacher about the James Webb Space Telescope. She had never heard of it, but smiled politely as her five-year-old student explained about the telescope’s infrared camera, the nature of the origami sun shield, and its potential to discover the first light in the universe. For years I bombarded countless people with facts about James Webb and its capabilities.

12 years after five-year-old Clair told Mrs. Chapelle about the telescope, I woke up on Christmas morning of 2021 to watch Webb lift off on an Ariane 5 Rocket.

Now in 2022, it fills me with joy to think about the great number of people who have recognized how groundbreaking Webb’s discoveries will be. People know that Webb had many delays and took over 2 decades to develop. They understand that engineers and scientists had to create new technology and develop innovations just to build the telescope. But most still cannot grasp the extent of the work from tireless individuals that went into the making of Webb. It is hard to fathom the number of people that dedicated their careers to its completion.

My mother Alison Nordt works at Lockheed Martin and was a program manager for NIRCam, Webb’s near- infrared camera. Its job is to detect infrared light and use it to peer into the past and capture images of the first light in the universe, images that might show the first stars and how they were created. NIRCam will answer questions, but also prompt questions nobody had thought to ask before. No pressure, NIRCam.

Webb’s story really began in 2000, when the Astrophysics Decadal Survey came out and NASA decided to prioritize building a next-generation space telescope. Lockheed Martin proposed and later won the contract to build NIRCam in 2002. For the next few years, optical designers and engineers designed the bench to which the instrument components would be mounted. The process was long, with complications such as designing a structure made out of beryllium, a toxic and brittle metal.

In 2004, the designs were drafted and a Preliminary Design Review was held by my mom and a team of others on June 30, 2004. That was just 11 days before I was born. After approval from NASA, manufacturing of the bench began in Cullman, Alabama. Over the following several years, my mom was in Alabama a lot. In fact, my toddler self developed a deep resentment for the state that kept taking her from me.

The Critical Design Review was in 2006. Like a test, NASA checked and approved the progress the NIRCam team had made since 2004. But a little while later, NIRCam hit a snag: the optical distortion, or WaveFront Error, was worse than expected. It took a lot of work, new innovative designs, exquisite optics manufacturing and alignment techniques for the team to fix it. “Those years were hell,” my mom tells me now. Meanwhile, I was in first grade, struggling to learn division and how to read a clock. Arguably also hell.

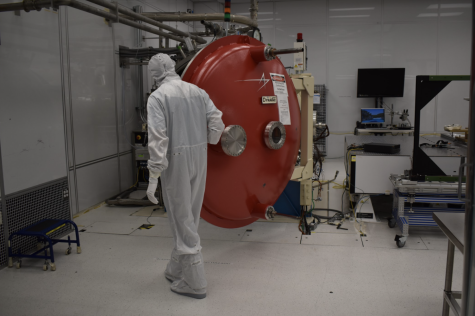

The next several years were filled with constructing and testing every part of the intricate instrument. Rare and exotic materials such as barium fluoride, lithium fluoride and zinc selenide were used along with metals like Gold, Aluminum, Beryllium and a great deal of Titanium. There was a lot of work with the 134 optical components, each of which had to be optically tested, then mounted, then tested again. In 2012, NIRCam was nearly finished and underwent cryogenic vacuum tests at 37 K in the Red Chamber.

NIRCam was built in Palo Alto, so during these years my mom didn’t travel as often.

In the spring of 2013, the two mirror-image halves of NIRCam were mounted back to back. I got to meet the instrument in -person that spring, right before NIRCam made its first voyage. Not yet to the stars, but to NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. After it arrived, NIRCam joined the other three instruments, MIRI, NIRSpec and FGS/NIRISS. They were put together in the spring of 2014 and completed the Integrated Science Instrument Module, or ISIM.

The next couple of years saw ISIM go through cryogenic and vibration testing. After everything was shaken to satisfaction, the telescope with its iconic gold mirrors and ISIM attached journeyed to the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. In 2018, after the final cryogenic test of the telescope and its instruments, the assembly traveled to Northrop Grumman in Redondo Beach, near Los Angeles to meet up with the spacecraft and sun shield.

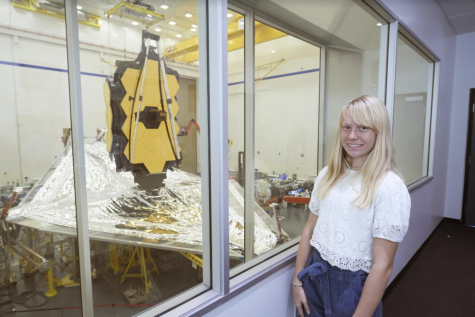

By 2019, my freshman year at NDB was drawing to a close. The mirrors, ISIM, sun shield and spacecraft were joined together and I had the opportunity to see the whole telescope. In late 2020, with COVID-19 restrictions in force, the observatory was subjected to another round of vibration tests. These tests ensured that the telescope could withstand the shaking of the Ariane 5 on its way to space. After all the testing, Webb faced the challenges of getting to South America and then getting into space. I faced the challenge that we like to call getting into college.

On October 5, 2021, Webb traveled through the Panama Canal and arrived shortly after in French Guiana. On Christmas morning, Webb left Earth, bound to solve amazing mysteries and undoubtedly create some of its own. I can’t wait to see pictures that will add a new chapter to our science books, 13.5 billion years in the making.

Looking back at our shared, much more recent history, Webb and I have grown up together. Like an older sibling, I can’t remember learning about the telescope; it has always been there.

After 17 years of my life and 20 of Webb’s, I can finally appreciate the hard work that my mother put into this project. Seeing Webb receive the attention it deserves in the last few months has been powerful, and has opened my eyes. I see just how groundbreaking this telescope’s discoveries will be. With my feelings for Alabama aside, I deeply respect the dedication that my mom put into the project. I hope one day I do something a fraction as amazing.

Clair Sapilewski is the Managing Editor and is in Journalism II this year. This is her third year writing articles for The NDB Catalyst.

She...

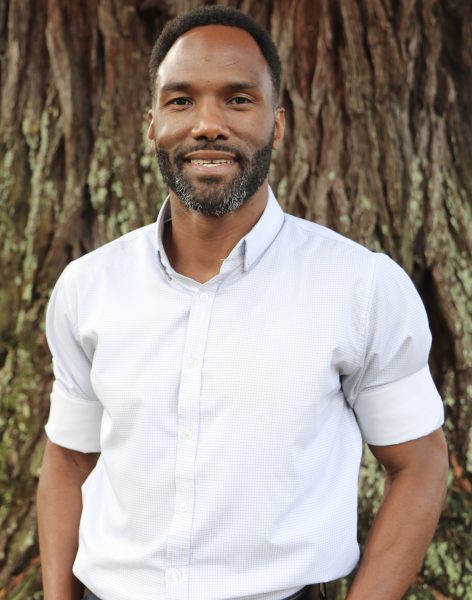

David Stubbs • Jun 20, 2024 at 4:04 pm

Claire,

Your mother is a powerhouse: boundless energy and enthusiasm with a keen mind to solve challenges, be they hardware or people-related. I had the great pleasure of working with her for many years.

You have obviously found your writing voice; straightforward and an enjoyable reading style. I see a very bright future ahead of you…

Jeff Jones • Feb 17, 2022 at 12:41 pm

I appreciate how you combine the science story with your human interest account of how the development of the JWST affected you in your life. Can’t wait to see the first images and to read your first book!

Jeff Jones • Feb 17, 2022 at 12:36 pm

Very well done. You combined the science with an interesting human interest angle. I can’t wait to see the images from the telescope and to read your first book! Keep writing.

Miguel Soldano • Feb 14, 2022 at 4:46 pm

Great article ! You can tell how proud you are of your mother.

Christian Halden • Feb 13, 2022 at 7:12 pm

Wow Clair! What a journey for you, your mom, and the JWST! I’m so excited to be even a small part of this journey!

Nelson Pedreiro • Feb 13, 2022 at 5:54 pm

What a great article. Well done and thank for sharing the insights.