The multi-billion dollar college admissions industry, fueled by record high numbers of applicants, an ever-shrinking job market, and the rise of hustle culture, has fostered a hyper-competitive environment.

With a steadily increasing pool of overqualified applicants vying for a numerically limited number of spots at top universities, the admissions landscape has become a battleground of perfect GPAs, flawless test scores and meticulously curated resumes. This has created an unprecedented level of competition within highly-ranked institutions.

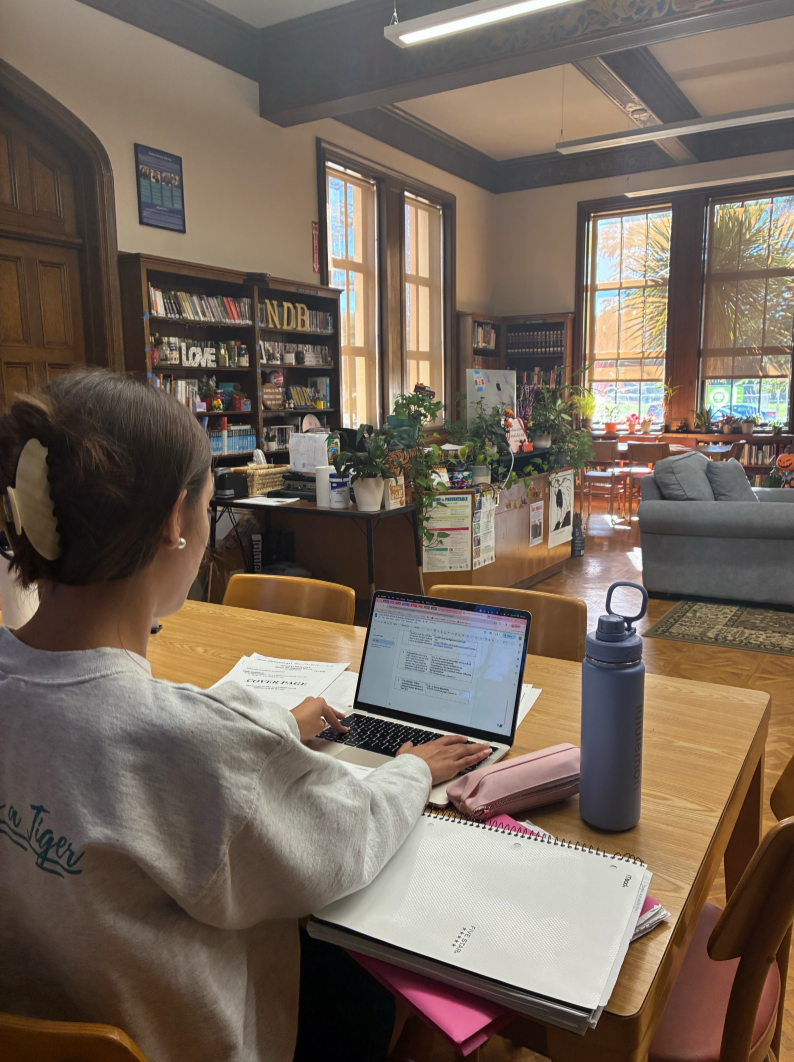

To gain an edge amongst the seemingly endless flow of impeccable applicants, families and students invest heavily their time, money and resources. Between private tutors and college counselors, wealthy families can spend tens – if not hundreds – of thousands of dollars to provide their children with the best chance possible of gaining admission to a top university. Students pile on as many AP classes and extracurriculars as their schedule allows, juggling hours of homework with numerous other clubs, sports and leadership positions. This pressure of a society that practically demands an Ivy League degree as a prerequisite for success is hugely detrimental to both students and families’ mental health and strains their resources.

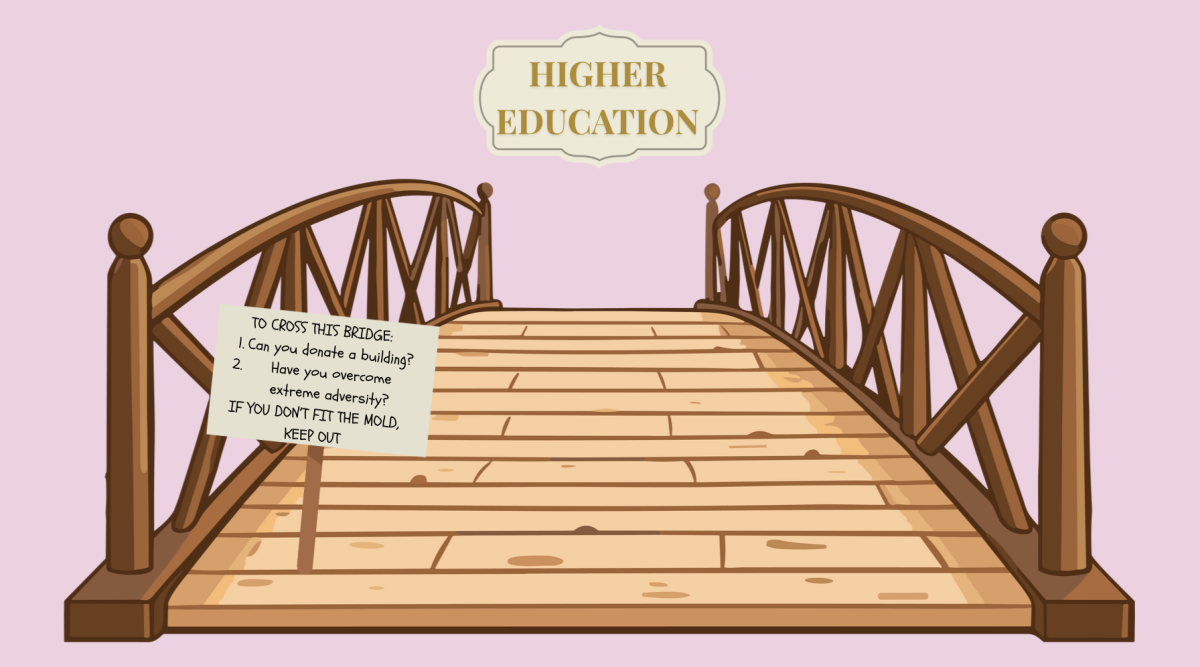

However, this increasingly competitive atmosphere has also fostered something much more harmful than previously thought. The system has created a three-tiered class divide – where the wealthiest and most underprivileged receive special considerations, leaving the middle class caught in between.

At the top of the social hierarchy, the wealthiest students often benefit from institutional priorities. A majority of private universities prioritize legacy applicants, as well as children of generous donors, when making admissions decisions. A preference for legacy applicants can have benefits: those who can make generous donations or pay full tuition allow for other students to enjoy more funding and increased opportunity. However, this practice, while within the right of a private institution to do so, can still unfairly reward lesser-qualified students with family connections over more qualified peers.

Conversely, many more universities have rightfully established systems in which underprivileged students are given special considerations, whether it be for a lack of access to resources, limited help in school and family responsibilities. The policy allows for a more level playing field, so to speak, and allows for less fortunate students to be judged on their achievements based on available opportunities.

Despite both practices having clear benefits – for both students and institutions – these can end up leaving middle class students and families with little aid in the process.

Many middle class families cannot apply for financial aid, as their household incomes are above the threshold for this qualification. However, many families are still unable to comfortably afford thousands of dollars worth of tuition and textbooks each year. This can put many students from middle-class backgrounds at a disadvantage, as they are unable to receive aid and cannot afford increasingly expensive fees for university.

Additionally, these middle class students do not receive any of the special admissions considerations that are extended to the other two groups. They are not viewed through the lens of overcoming significant adversity, nor do they benefit from the institutional preferences granted to legacy or donor-affiliated applicants.

This “middle-class squeeze” leaves them in a precarious position. They are expected to compete with the outputs of the wealthy—who can afford expensive private counselors, test preparation, and resume-building summer programs—but without the same financial resources.

Simultaneously, they lack the “disadvantaged” status that would allow admissions committees to contextualize their achievements. They are judged on a scale of absolute merit that, in reality, is heavily skewed by wealth and access.

The result is a cohort of students and families who feel systematically overlooked. They bear the full weight of the hyper-competitive expectations but receive neither the financial relief of the underprivileged nor the preferential treatment of the elite. This can lead to immense pressure to take on crippling student loan debt, straining family finances for decades.

Ultimately, this three-tiered divide undermines the very promise of higher education as an engine of meritocracy and social mobility. Instead of leveling the playing field, the current admissions landscape often reinforces existing class structures, rewarding inherited privilege at the top and offering conditional pathways at the bottom, all while the broad middle is left to navigate a system that seems stacked against them.

Until universities fundamentally reassess their priorities—moving away from practices like legacy preference and developing more nuanced financial aid models that support middle-income families—the admissions “game” will continue to be one that not all qualified students have a fair chance to win.