Movie-watching, once a deeply engaging experience, is losing its allure among today’s youth, as short-form content on platforms like TikTok and Instagram reshape how they consume media. For many teens accustomed to bite-sized entertainment, the idea of sitting through a full-length film feels increasingly daunting.

Social media’s rapid pace and endless novelty appeal especially to younger audiences, who often spend hours scrolling through curated feeds. This constant exposure to brief, high-intensity content conditions teens to crave instant gratification, making the slower pacing and layered narratives of movies seem tedious by comparison.

“I’m checking my phone at least 10 times around a movie,” admits junior Isabella Michael.

This frequent device use disrupts the ability to fully immerse in films, a skill that younger generations struggle with more than their predecessors. For many teens, the impulse to multitask—whether by glancing at notifications or scrolling mid-scene—has become second nature.

Yet, as AP Psychology teacher Melony Flint points out, “All that is happening is when we consider ourselves to be multitasking, what we’re really doing is … purposely giving ourselves ADHD.”

The brain’s inability to truly focus on multiple tasks means that even brief distractions come at the cost of missing key cinematic elements. In film, where every detail—whether visual, auditory, or emotional—plays a role in the storytelling, divided attention weakens the overall experience. For teens raised alongside smartphones and streaming platforms, unlearning this habit poses a significant challenge.

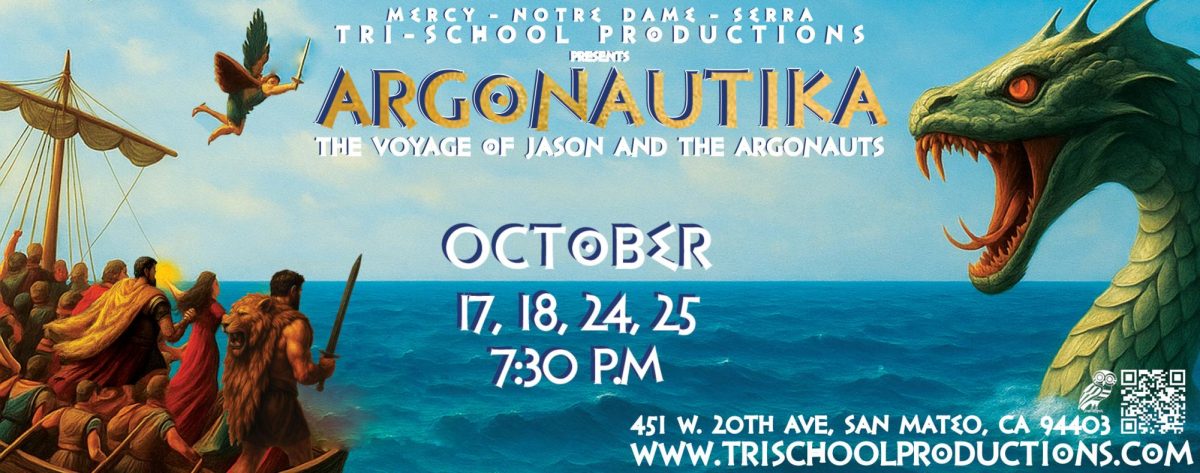

“I think that appreciation for the art of movies and media is kind of being lost through this short media,” says freshman class president August Kelly. “It’s becoming a lot less popular because you can access short dopamine from watching TikTok … instead of staying and watching a beautiful, excellent movie.”

Kelly’s point underscores a broader cultural shift. Movies require patience and an eye for detail—qualities that are becoming rare in a world dominated by swiping and scrolling. Without these, viewers risk overlooking the incredible craftsmanship behind filmmaking.

“If you’re watching a movie, and the filmmakers have put such hard work into putting little details in the movie that can be all tied together at the end, I think that you can miss a lot of that and kind of miss the overall point and beauty of the movie,” adds Kelly.

Flint offers a similar perspective, emphasizing the role of nonverbal communication in storytelling.

“Communication is 80% body language and 20% verbal … if you’re watching a film and you’re not watching it, you’re gonna miss that somebody in that moment felt sad when somebody walked away,” she explains.

These missed nuances aren’t minor—they often form the heart of a film’s emotional resonance. By failing to engage fully, audiences lose opportunities to connect deeply with characters, stories, and themes.

The consequences of this shift extend beyond personal habits. Films have historically been a mirror to society, challenging viewers to grapple with complex ideas and broaden their perspectives—something especially valuable for young people navigating today’s fragmented cultural landscape. When attention spans shrink, cinema’s potential to foster empathy and understanding diminishes.

The art of movie-making is more than entertainment; it’s a vehicle for connection, introspection, and growth. To preserve its relevance in the age of short-form media, reclaiming focus and patience is essential—not just for the films themselves, but for the lessons they offer.